One dimensional motion is built upon four very important measurements: velocity, time, displacement, and average acceleration. Before jumping into the discussion on these measurements, it should be made known that all of these measurements, except for time, are vectors. Vectors are measurements that describe both magnitude (size or value) and direction. The other type of measurements are scalars which describe only magnitude.

An example of a vector: The ball was sent flying at 10 km per hour to the east. An example of a scalar: The ball was sent flying at 10 km per hour. Hopefully this gives a basic idea of vectors vs scalars. Velocity, displacement, and acceleration: velocity is the vector for speed, displacement is the vector for distance, and acceleration can act as both a vector and a scalar but since all of the other measurements are vectors, acceleration will be treated as a vector.

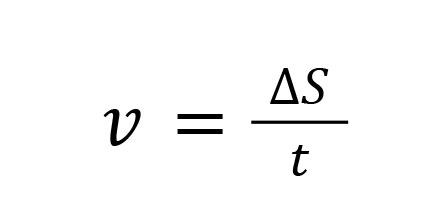

Hopefully the above information provided the proper basic knowledge of vectors and scalars in order to continue this discussion. Velocity is described as change in displacement per a given amount of time. Mathematically, velocity can be described as:

Where 𝑣 is velocity, ∆𝑆 is the change in displacement (∆ is the Greek letter delta and symbolizes “change in” and 𝑆 stands for displacement), and 𝑡 is time.

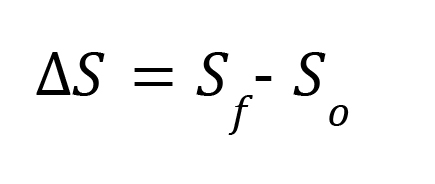

To calculate the change in displacement, the following equation can be used:

Where ∆𝑆 is the change in displacement, 𝑆𝑓 is the final displacement, and 𝑆𝑜is the initial

displacement (the displacement at 𝑡 = 0).

Let’s do an example of calculating velocity:

A car drives 80 kilometers to the north. It takes the car 20 minutes to reach its destination, what was the velocity of the car in kilometers per minute?

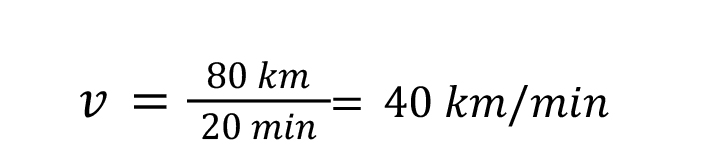

To start, the car drove 80 kilometers, so we can use that to calculate the change in displacement. Now, it is intuitive that the car did not travel anywhere in exactly zero seconds, so 𝑆𝑜 = 0. The final displacement is already known: 80 km. With this information:

∆𝑆 = 80 𝑘𝑚 − 0 𝑘𝑚 = 80 𝑘𝑚

The time it took for the car to reach its 80 kilometer destination is 20 minutes, so 𝑡 = 20. With all of this information, the values can be plugged in:

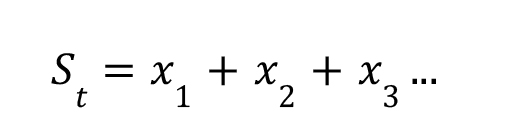

Hopefully you can see that calculating velocity like this is a very straightforward process. For many problems, such as the one above, the initial displacement is equal to zero. However, there are problems where the displacement will need to be calculated as total displacement ( 𝑆𝑡 ). In a

one dimensional setting,

Where 𝑥𝑛 (and 𝑛 is any positive integer such as the ones shown above) is the path of travel for an object.

Before we can get into an example, the difference between total displacement and total distance should be addressed. When talking about displacement in a one dimensional setting, an object moving to the right has a positive value and an object moving left has a negative value. Thus, when calculating total displacement, if an object travels to the right and then to the left, there will be addition of negative and positive values. On the other hand, because distance is a scalar and does not take into account direction, it cannot be negative. Thus, if an object travels to the right and then the left, it will be an addition of positive values.

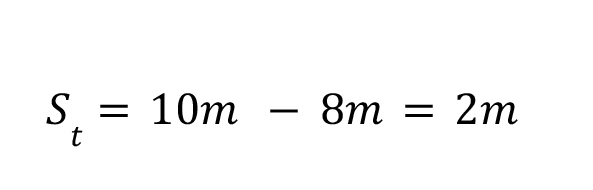

Example: A ball moves 10 meters to the right, but is then kicked back to the left. What is the total displacement of the ball?

Well, if we use the equation above, there are two paths of travel: 𝑥1, which is 10 meters to the

right, and 𝑥2, which is 8 meters to the left (a negative value). Now all we have to do is plug these values in:

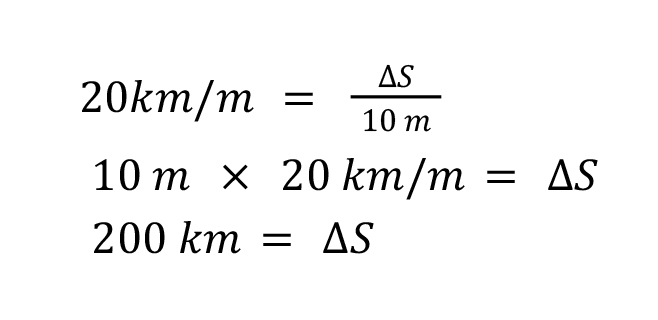

There is an alternative way to find the displacement and that is to rearrange the velocity equation to solve for displacement. Example: A car travels a total at a constant velocity of 20 km per minute for a total of 10minutes, what was the change in displacement?

Well, we know the time and the velocity, so we can plug those values in and solve from there:

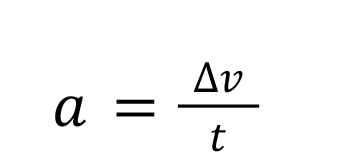

The last very important aspect of one dimensional motion is average acceleration. We have all heard of acceleration before. When an object is in motion, its speed tends to change (be non-constant) over time due to external forces. Mathematically, average acceleration is described as:

Where 𝑎 is the average acceleration and ∆𝑣 is the change in velocity. Change in velocity is very similar to calculating change in displacement, all you have to do is subtract the initial velocity from the final velocity:

∆𝑣 =𝑣𝑓 −𝑣0

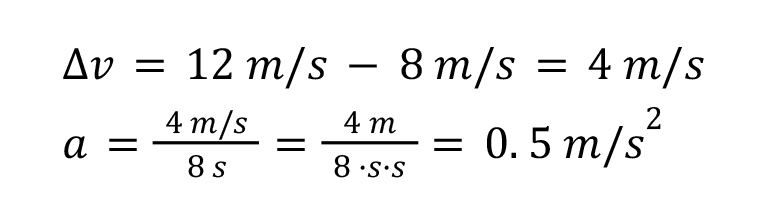

Let’s do an example of calculating acceleration: An object travels for 8 seconds. It starts out with a velocity of 6 meters per second and then constantly accelerates until it reaches a final velocity of 12 meters per second. What is the object’s average acceleration?

The problem provides us with key information: it travels for a time of 8 seconds, the initial velocity is 6 meters per second, and the final velocity is 12 meters per second. This is enough for us to solve the average acceleration:

Notice how the units are meters per second squared. Now this might seem like it is kind of unintuitive, but think about it this way: acceleration describes how many meters per second that the velocity changes every second.

This is honestly dope jack! The website and articles look great man.

LikeLiked by 1 person